Spinors

Definition

See this mathstackexchange answer.

Let $Spin(n)$ denote the spin group (the 2-fold covering group) of $SO(n)$. Then spinors (with respect to the group $Spin(n)$) are elements of a vector space $V$ on which $Spin(n)$ acts via a (usually) irreducible finite-dimensional linear representation $(V,\rho)$ which does not descend to a representation of $SO(n)$. (In this generality, the notion of a spinor depends on the particular choice of a linear representation.)

In most cases, $V$ is taken to be a fundamental representation of $Spin(n)$ constructed via the Clifford algebra $Cl(n)$. See Clifford algebra#The spin group and the spinors.

Thus, spinors are not elements of the spin-group. Regarding spinors as such is an abuse of notation which one should avoid.

One frequently generalizes this definition of spinors to include not just vectors (in a suitable vector space $V$) but spinor fields which are (smooth) sections of some vector bundle over an $n$-dimensional Lorentzian manifold $M$. Such a vector bundle is derived from a spinor representation $(V,\rho)$ via the associated bundle construction applied to the principal bundle with group $Spin(n)$. With this definition, in local coordinates, spinors appear as (smooth) maps

$$ U_\alpha\subset R^n\to V, $$which transform, under local change of coordinates, according to the spinor representation $(V,\rho)$.

Edit. The nicest detailed treatment of spinors that I know, from the mathematical viewpoint, is in the book:

1. _Lawson, H. Blaine jun.; Michelsohn, Marie-Louise_, Spin geometry, Princeton Mathematical Series. 38. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. xii, 427 p. (1989). ZBL0688.57001.

Specifically: Chapter I, sections 1-6 (explaining spin groups and their representations); Chapter II, section 1, 3, finally defining spinor fields. (This is before you get to the Dirac operators; Dirac operators are covered in sections 4-7 of Chapter II.)

Disconnected ideas

According to this eigenchris video, they are elements of the projective complex line $\mathbb P \mathbb C^2$, in other words, the Bloch sphere.

Spinor space can be thought as the set of quantum states of a two-level quantum system, like the spin of the electron.

In other contexts, spinors are, simply, $\mathbb C^2$... I think that spinors are indeed elements of $\mathbb C^2$, but when they represent quantum states we assume that the multiplication by a complex number doesn't change the state.

... To be developed...

But physicists also refer to spinors as section of a spinor bundle. They transform under the spin group.

Related: Pauli matrices.

Another definition: element of minimal left ideal in a Clifford algebra (here

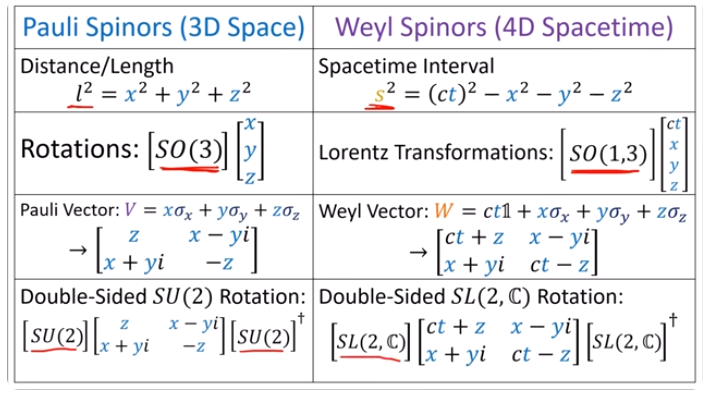

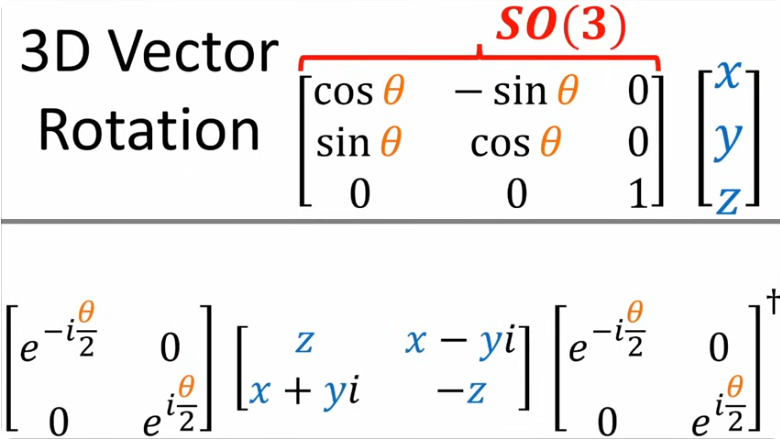

Pauli spinors vs Weyl spinors

From this eigenchris video.

There are also the Dirac spinors, related to the Dirac equation.

Physical realization

Light polarization

Stern-Gerlach experiment

Let's suppose that we feed a Stern-Gerlach machine with a beam of electrons prepared in a specific state; we will get two outcomes with different frequencies (probabilities). These outcomes and their probabilities are encoded in a vector of a Hilbert space. When I rotate the electron gun with a different spatial orientation (in our everyday 3D space), the probabilities change, suggesting that the electron is in a different state, another vector of the Hilbert space. However, the angle formed by this vector compared to the original one is half of the spatial rotation. We can say that on the 3D vectors of everyday life we are applying an element of SO(3), and on the Hilbert space, we are applying an element of SU(2), which is its covering space. The question is that starting from the initial orientation, I can reach the final orientation in many different ways. For example, I can stay as I am, which is a rotation of 0º, and that implies a 0º rotation in the electron's internal state; or I can rotate the electron gun 360º around any axis, which would mean having rotated the electron's internal state by 180º. Although the gun is in the same position and orientation as before, internally the electron is in a different state. This won't be noticeable in a simple experiment because global phases don't show, but it could influence an interference experiment.

How do those experiments roughly go?

(see in calibre the pdf: "Spin rotation subtleties, Spin entanglement- experiments phase shift". See also this video of Leonard Susskind)

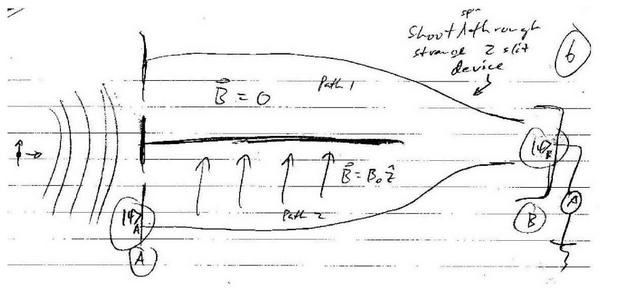

What happens if we take the spin wavefunction of a particle, break it into two pieces, and let it interfere with itself? How can you do this? Use a classic two-slit experiment. You can observe strange interference effects. Imagine the following peculiar device:

The particle starts in the spin-up state $\psi_A = |0\rangle$. What we will do is shoot spins through the device and measure the number of spins that get through to point B:

$$ \psi_B = e^{-iH\hat{t}/\hbar} = \psi_A = \psi_{\text{path1}} + \psi_{\text{path2}} $$This is the classic description of interference, where we superpose two quantum states and see if they constructively or destructively interfere. But what are the quantum states for the two paths?

$$ \psi_{\text{path1}} = |0\rangle $$and

$$ \psi_{\text{path2}} = e^{-i\hat{S}_z \hbar \Delta\phi} |0\rangle $$where $\Delta\phi = \frac{eB_0}{m} \Delta t$ and $\Delta t$ is the transit time.

Now let's suppose that $B_0$ and $\Delta t$ are tuned so that $\Delta\phi = 2\pi$. What happens? Naively, we might think nothing would happen because a $2\pi$ rotation brings you right back to where you started. However, this would be incorrect. We need to note the following:

$$ \psi_{\text{path2}} = e^{-i\hat{S}_z \hbar \cdot 2\pi} |0\rangle = e^{-i\pi} |0\rangle $$So $\psi_{\text{path2}} = -|0\rangle$! Normally, we ignore the "-" sign since it's an overall phase factor, but now we can't since the particle is going to interfere with itself. So what happens at point B?

$$ \psi_B = |0\rangle + (-|0\rangle) = 0 $$How many particles get through? ZERO!

This phenomenon has been experimentally observed in what are now classic experiments with neutrons.

See H. Rauch et al., Phys. Lett. 64A, 425 (1975) and S. A. Werner et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 35, 1053 (1975).

________________________________________

________________________________________

________________________________________

Author of the notes: Antonio J. Pan-Collantes

INDEX: